Autoethnography: Impressions of Time Spent near the Holy Yamuna River

Northwest Vista College & Creighton University

July 17, 2022

To awaken quite alone in a strange town is one of the pleasantest sensations in the world. You are surrounded by adventure. You have no idea of what is in store for you, but you will, if you are wise and know the art of travel, let yourself go on the stream of the unknown and accept whatever comes in the spirit in which the gods may offer it. (Stark, 1937, p. 17)

“Hello, how old are you?”

Among the chaos of dozens of Hindi (and other language) speaking yatris, or religious pilgrims surrounding me, mule bells jangling, music playing, men yelling commands to their mules, and palki-bearing porters yelling “sap, sap, sap” (something akin to breathe, breathe, breathe with a meaning of go, go, go) I knew if I heard someone speaking English the person was speaking to me.

I looked around for whoever asked the question, and it

was a professional looking Indian man, dressed in Western clothing, a collared

button-down shirt, nice grey slacks, and dress shoes—he could have been a

dentist or an accountant. He was on his way up to the Yamunotri Temple some 5

km (3.1 mi) and over 1,580 m (5,200 ft) in elevation gain.

|

| Yatris, or pilgrims, being carried 5 km from Janki Chatti to Yamunotri. |

Struck by the odd question—I usually get “where are you from?”—I asked back, “How old are you?” with a bit of a quizzical look on my face, I’m sure. He promptly said “62.” I told him I was 56. “Are you coming from Yamunotri?” I responded, “yes.” He said, “Okay then, if you can make it so can I.” I found it a bit humorous that he was using me, likely the only White guy in the entire region and among the thousands of pilgrims on the trail, as a measuring stick to determine if he could make the trek to the 139-year-old temple that sits at 3,235 m (10,614 ft) in elevation. I told him, “Yes, but I left at 10 am,” and showed him my watch—it was 3:45 pm. He said, “no problem, I should be back just after midnight” and off he went up the crowded path on his tirtha-yatra.

The nonchalant attitude and determination, if not pure devotion (and personal expense), to make the 10 km (6.2 mi) round trip pilgrimage on foot to the tirtha seems to run common in the demeanor of the yatris. The yatris are the pilgrims themselves, on their yatra, or procession/pilgrimage, to the tirtha, a literal ford or stream crossing place that is sacred—where one can metaphorically cross over to liberation of the other shore. In this case, it was the goddess Yamuna’s temple at Yamunotri where one crosses the river of the same name.

I sit now, in the cold and dark of my room overlooking the yatra route. The electricity has been out for about two hours due to the monsoon rains and the cloud-obscured sun is fast going down behind the mountain peaks along with the temperature. My mini-camping thermometer reads 12.7°C (55°F) and my feet are cold. I can see from my vantage, a choke point bridge where well over 1,500 people passed through in one hour this morning. In a 15-minute observation, I counted 216 yatris. One can determine the yatris from the mass of porters based on their clothing and accessories (clean, many men with shirt creases from being folded in a suitcase, sunglasses, tennis shoes, water bottles, etc.) or by their actions (walking while video recording with mobile phones, taking pictures of one another, or talking on their phones). Although many yatris represent a cross-section of India, there are few female workers here, so any woman spotted is likely doing their yantra.

|

| Yatris crossing bridge along the pilgrim path. |

There is also a representation of older Indians. They move slow but steady up the trail with a look of determination of their face. Of the yatris, 80 were on mule back, each with a guide. Twenty-one yatris were being carried in a palki or doli, the local term for a crude uncovered palanquin or litter carried by four men, and seven were being carried in a tumpline basket on the back of a hunched over Nepali man. All the basket bearers were Nepali immigrants, and apparently they have the well-deserved reputation around here for being the most bad-assed of the influx of seasonal service-oriented entrepreneurs. Imagine carrying a person on your back the entire distance up to the temple. All told, in 15 minutes 387 people crossed the bridge going up the trail. Extrapolated over one of the busiest hours of the day that comes to well over 1,500 people moving up the trail.

|

| Barefooted yatri. |

That is, those who wore shoes. One of the

purist forms of yatra is the padayatra, doing the yatra barefoot. Padayatra

is tapasya, a form of self-suffering that I observed some people doing.

In my Western mindset, grounded in a United States of America, Judeo-Christian,

White, male dominated culture, I cannot for the life of me imagine anyone in

the US walking 5 km up 1,580 m of elevation on a twisting, mule-dung covered trail

to well over 3,235 m of breath-stealing elevation to the dhama, dwelling

place, to passively receive blessings from a female goddess statue after

bathing in a frigid, glacier-born river for purification. In fact, I cannot

imagine Americans walking 5 km for any religious purpose whatsoever, much less

having the singularity of devotion it must take to pursue such a trek. That, most

especially after making a bus trek along a landslide laden (Uniyal et al.,

2012), sometimes single-track “highway,” of motion sickness inducing twists and

turns with a machoistic driver hell bent on getting to the parking lot at the

staging point in Janki Chatti first.

This dérive, drift, or self-styled non-religious yatra I am on now is part of a digital humanities fellowship research project I conducted in 2022.

In a dérive one or more persons

during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure

activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let

themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they

find there. (Debord, 1958, p. 1)

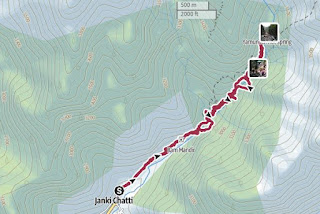

|

| Dérive to Yamunotri. |

|

| Dérive elevation profile. |

Flip Flops for Hiking

While my entire gran dérive from New Delhi to Yamunotri and back offered insight to my cultural understanding of India, I took a long walk about every other day while in the field to gain other experiences and meet other people—call these petit dérives if you will. On one such drift within a drift, I walked, or trekked as the muleteers and porters I was living with phrased it, along a quiet mountain trail through an ancient Indian village, over the raging Hiranyabahu River, a tributary to the Yamuna River, and up an unnamed peak to see if I could get to the tree line for a better view of the snow-covered Bandarpunch massive, a three-peak mountain range with Bandarpunch II (White Peak) at 6,102 m (20,020 ft) being most prominent.

|

| Bandarpunch II hidden in clouds. |

I discovered walking for the sake of walking is not a thing in rural India. Typically, one has a destination. While I was aiming for the tree line as a destination my purpose was simply to walk and get away from the chaos of the pilgrim trail and to just be in the forest alone. Along the way I ran into three diminutive women, each bearing a stack of firewood on a tumpline strapped across their forehead. They were chatting away, seemingly happy, wearing the clothing of the local women from the village below, muted colors save for their bright green and red head coverings, and flip flops, except for one who was barefoot. I expected them to go silent when I approached, but rather they started laughing, chattering louder, and making hand gestures toward the top of the mountain, smiling the whole time. I had no idea what they were talking about, I smiled, hand gestured toward the top of the mountain myself, and kept walking. The impression I was left with though was their footwear, or lack thereof. Often villagers would quickly glance at my shoes—I hike in blue trail running shoes, not hiking boots or flip flops. These women left a big enough impression on me that I recorded my thoughts as I proceeded down the trail. I was thinking how materialistic we are in the United States. How the market for outdoor footwear is so immense, and how outdoor clothing retailers like Recreational Equipment Incorporated (REI) profit from the sales of specialized footwear and specialized socks, and how we as a culture think we need those things. I am not advocating for barefoot hiking, it seems if you have not walked around for years barefoot like the one woman I met it would be difficult if not cutting and bruising, to hike a rocky mountain trail barefoot. However, in an oxymoronic way, the US market does offer “barefoot running shoes,” and I must chuckle at the ludicrousness of the notion as I write this. “These types of shoes put the fun back into your regular morning runs when discovering new trails” reads the copy of GearHungry.com’s (Gearhungry staff, 2019) review of barefoot shoes. (The title of the website is telling—Gear Hungry—an insatiable thirst for stuff.) I cringe to think what that barefoot mountain woman would think of barefoot shoes, each with five toe slots like gloves for one’s feet. She might actually like a pair of them, but the notion of people wanting to mimic her lack of resources for “balance and a better connection with your terrain” and so one’s toes can “relax while running,” seems absurd to me.

|

| Dérive to beyond Kharsali. |

|

| Dérive to beyond Kharsali elevation profile. |

Incidentally, I never made it to the tree line. I was

just shy of it when it started to thunder. With thunder comes lightening which

I did not want to encounter on a bare-naked mountainside. I beat a path back

down the mountain and only experienced some light rain—and wet shoes.

Kidnapping

On another of my petit dérives I was kidnapped.

This time, rather than crossing the Hiranyabahu River I was in search of a trekking route up and alongside it. Again, starting off through the village of Kharsali I worked my way along a cliff above the river on a well-defined trail I was able to clearly see from my previous trek. This one climbed gently through ancient, terraced fields of potatoes and wheat. The terraces themselves amaze me. As I walked, I thought of the ancients who carved the slope of the mountainside to level one shovel full of soil at a time. Using Google Earth I calculated that 35.6 hectares (88 acres) of the land above Kharsali had been terraced over time. More terracing had been abandoned further away from Kharsali in what used to be known as the village of Beef, which no longer exists.

|

| Kharsali women harvesting wheat in terraced plots. |

On this trek I was photographing women harvesting wheat far below when an old man passed me as he headed up the trail. He acknowledged me, said something friendly in a language I did not understand, and went about his business sauntering deliberately up the trail, hands clasped behind his back. Moments later he was headed back down the trail carrying plants he had foraged. He struck up a one-sided conversation with me, as I had no idea what he was saying. With gestures I asked if I could take his photograph and he agreed. I did. Then he said “chai,” which I understood, as he gestured back down the trail toward the village. I smiled and tried to decline the invitation several times, however, he insisted. He approached me, took me by the hand and started walking down the trail toward Kharsali with me in tow. There I was, walking hand-in-hand with a man who looked to be as ancient as the terraces surrounding us. In India it is common for men to walk hand-in-hand or arm-in-arm, so I acquiesced and proceeded down the trail with him. He only let go of me to forage for plants.

|

| Mr. Chandan Singh. My kidnapper. |

We walked toward the village and an equally old woman

approached. They stood in the trail and had an animated chat. That allowed me

time for reflection; I could only wonder what they were talking about, but she

never looked at me. Nevertheless, I was thinking of the situation…one goes out

in the morning to forage for trailside plants, picks up a foreigner and invites

him over for tea, has a conversation with someone they probably have known for

decades, then proceeds to guide the stranger to their front porch in a house

that appeared to be well over 100 years old. I really do not know how old the

older homes in Kharsali were, but they were designed with slate stone roofs and

for livestock to live on the first floor with the humans living on the second

floor. I have seen this type of living situation in the Pyrenees and Picos de

Europa ranges in Spain, and other old-world cold weather locations. However, in

India where modern homes are boxes built of rebar and concrete with flat

concrete roofs, the homes in Kharsali were the first I had seen with the first-floor

livestock design. Nevertheless, I was invited to the porch for tea. I was given

the only chair while Mr. Chandan Singh and his wife sat on mats of the ground. His

daughter brewed up some chai, which took some time. While we were waiting and

trying to have a conversation with Google Translate on my phone—a comical event

at best—other people started materializing. I would look up from trying to type

English in Translate and another woman would be sitting at the other end of the

porch. Then another, then the man from next door, then two teenaged grandchildren.

In short order the porch was full of people sitting on mats on the floor and me

in a chair as if I were at the head of the table.

|

| Conversation along the path back to Mr. Singh's house. |

I was happy to have been invited to have an experience on Mr. Singh’s porch. However, the two grandsons were more interested in the brand of my phone and in my camera. The older one took it upon himself to remove the SIM card from my camera and tried to figure out how to put his phone’s micro-SIM in it so he could have a picture of himself. Happy to take a picture of him, the best way was via my phone so I could send it to him via WhatsApp. He would not have it and wanted one with the “SLR,” I suppose he perceived it as better quality. By this time the others on the porch had lost interest in me because it was too difficult to have a conversation via Google Translate. The boys wanted to take my camera and go show some friends. I told them nahin (no in Hindi) and had to actually take my camera back from him before he tried to take off with it, which is what he was indicating. Then he started asking for money. Then his younger brother started asking for money. I was struck by the dichotomy of the grandfather’s selfless offering of tea on his porch and his grandsons’ selfishly asking for money. As a rule, I do not hand out money to children who ask for it in any developing region. The situation can be a conundrum, but I have chosen not to hand out cash. At that point I decided it was time to take my leave. I thanked Mr. Singh and his wife, stepped over the women on the porch and made my way down the steps only to be followed by the younger boy who continued to ask for money as I walked. Eventually it began to rain, and he ran off to seek shelter.

|

| Mr. Singh and his wife on their front porch. |

|

| A sample of the plants Mr. Singh was collecting. I think what he foraged was, in order left to right, wormseed wallflower, absinthe wormwood, lambs’ ear, pink jasmine at the bottom. |

|

| Suddenly the front porch is full of people over for tea, including the grandsons. |

River of Love in the Age of Pollution

“Rivers have been worshipped as sacred entities for millennia worldwide, river worship is a more prominent feature of Indian culture than of any other culture in the world today.” This is…

…true of the Yamuna River, which is conceptualized religiously as a divine goddess flowing with liquid love. Today, however, we live in a complicated world, a world in which sacred rivers have become severely polluted. This too is true of the Yamuna.

|

| Depiction of the goddess Yamunotri. Note the Yamuna River running in the background. |

These are the opening words of religious scholar David

Haberman (2006, p. 1), who in 1996, toured by bicycle down part of the length

of the Yamuna River contemplating the complex interrelationship between

religion and ecology. Being a long-time religious scholar, Haberman articulated

the concurrence between river worship and river pollution, often by the same

people, much better and in more depth (and with substantially more academic

insight) than I ever could. However, as I trekked up the trail from Janki

Chatti to the Yamunotri temple this juxtaposition was fore on my mind. From my Western

perspective I could not fathom how people on a trek that requires considerable

time and expense, much less physical exertion, could tolerate the landslides of

trash, sewage, and mule dung on their way to pay tribute to the goddess of the

river herself. For me the trail of filth was off putting to the point that when

I was invited by Himachali

Dharmshala Hotel and Canteen operator and manager Vikash Nautiyal to

go with him for a private tour of the Yamunotri temple and hot water baths, I

declined. Not once, but three times. His uncles are pujaris (priests) at the

Yamunotri temple, so my decline of his offer was likely substantial and

perplexing to him. Perhaps a cultural faux pas, but I opted instead for the

treks I described above, away from the pollution, sewage, and noise. At that

point I had had it with flies, mule feces, and getting shoved around on the

overcrowded trail by doli walas, ghoda walas, and their

mules, not to mention the constant smell of barn that permeated the air and my

room. The cultural cognitive dissonance I was experiencing at the time was

palpable.

|

| Thousands of flies cover everything in and around the pilgrimage trail. |

Quoting again from Haberman because I concur with his statement, “I want to make clear that I do not mean to be overly critical of India: the problems of river pollution are found everywhere” (2006, p. 16). In 2010, I was in the Mexican village of Colatlán, Vera Cruz conducting a rapid rural assessment of river pollution at the invitation of the Partners of the Americas. There, in the corn-based, indigenous Nahuatl culture, I was conducting interviews related to residents’ perceptions of why the water in the river was so polluted, the groundwater polluted, and both nearly running dry. To me the problem was painfully obvious, 4-inch pipes from home toilets were flushing straight into the river, years of drought, and lightly terraced hillsides completely stripped of vegetation, save for corn plants, where any rainfall would just run off rather than soak in. However, understanding the indigenous perspective is paramount in helping to develop locally accepted solutions. I spoke with the resident shaman who told me when people began to throw trash in the river the river goddess Apanchenej just up and left. She was offended and left the water without her protection. Apanchenej’s absence came up more than once, even with the Nahuatl women washing clothes riverside in water that reeked of sewage. The fact that a recently built slaughterhouse that supplied jobs but did not have any retention ponds for animal fecal material or slaughter waste products, did not help the situation.

Where the Yamuna River ran alongside Janki Chatti I found a curious structure I at first thought was designed for flood protection and diversion. Out of curiosity I battled past a couple of loose mules intent on using the dam-like structure as an easy pathway to avoid the river boulders below, as I was doing. Water was being diverted from the river into a concrete channel that became a concrete tunnel. A large metal pipe, probably three feet in diameter, joined the tunnel of river water then spilled out in a human-made cascade just a few dozen meters downstream, the water mixing back with the main flow of the river. A young man, an obvious yatri by the way he was dressed, approached me and asked the typical question, “where are you from?” I answered and we had a bit of a conversation. He was waiting on his mother and father to catch up with him so they could all bathe in the frigid holy Yamuna as a monsoon drizzle began to chill the air. I asked him if he knew what the diversion/piping structure was and without hesitation he said, pointing to the cascade of water flowing back into the river, that is nala—dirty water. Google Translate later confirmed for me that nala (नाला) is in fact the Hindi word for sewage as I suspected. If one discounts the drizzle of grey water, black water, and mule dung runoff from the 5 km of Yamunotri pilgrimage trail, along with the avalanches of trash swept and shoveled over the edge into the ravines, this was the point where raw sewage was mixed with the pure holiness of Yamuna to defile the river for the rest of its journey. At least she has not abandoned the water upstream yet. I suppose it is fortunate that Yamuna and Apanchenej occupy different cosmologies, lest they otherwise get together, talk, and both decide to abandon their age-old watery places due to their followers’ transgressions, each leaving a spiritual vacuum behind.

|

| Nala water diversion structure. |

|

| Where the Yamuna River becomes less holy and sewage starts. |

I watched as the father of young man I had just met stripped down to his underwear and dunked himself into the river upstream of the nala. Fully clothed, the young man’s mother submerged herself in the river with the help of her two sons. They all stood in the river for a few minutes splashing the goddess’s pure love onto their heads before the cold drove them back up on the rocks.

|

| Yatris down by the river just above the nala site. |

When I was at the Yamunotri temple a few days prior I

watched as dozens of yatris stripped down to perform ritual bathing in the glacial

meltwater that is the Yamuna River. While some just kneeled to touch the water,

others splashed her onto their heads. The brave submerged their entire body into

the cold rushing water. Even the god Shani, brother of Yamuna in the form of a

brass mask, is bathed in the river at Yamunotri before he returns to Kharsali

each year in an ornately decorated palanquin after dropping his sister off

there at the end of the winter. Like Baptism to a Christian, the waters of the

Yamuna are thought to wash away sins and protect one against anguish after death.

Haberman maintains a hopeful position that the holiness of the Yamuna will save it from pollution. He wrote that “we need to respond with love to the now-damaged world in which we live,” and that the “strongest love is one that can take the pollution into itself, neither denying it nor succumbing to disempowering depression” (2006, p. 194). Nugteren wrote, “While loving devotion to embodied divinity in India may often be more effective than the scientific approach, it is definitely not a panacea” (2008, p. 531). Haberman’s notion seems naïve to me as I witnessed thousands of pilgrims casually walk past their own pollution on their way to worship, demonstrating what appeared to be a worldview that even though they worship the river and become one with it through bathing, they still see themselves separate from it.

Fish Fair

One-hundred twenty kilometers (74.5 miles) south from

Janki Chatti, yet four hours by jeep taxi through the hairpin curves of the

mountain road toward the hill station of Mussoorie, lies the village of Sainji

Gaon. Sainji is perched on the steep hillsides of the Himalayan foothills at 1,200

m (3937 ft) above sea level and 500 m (1,640 ft) above the Aglad River that runs

into the Yamuna River just a few kilometers downstream. I was staying in Sainji

to work on writing my case study in a place that was not as cold and rainy as

Janki Chatti in the monsoon. I learned from one of the village leaders that

there was a regional “fish fair” coming up where men from villages all over the

area converge on a short stretch of the Aglad to “fish” in an annual event that

has been going on for a hundred years. I am putting “fishing” in quotation

marks because the villagers poison the river with timaru, a plant-based powder

they make themselves. Men stand in the river with nets and attempt to catch as

many dead and dying fish as possible. I thought this is a cultural event I

could not miss, and it led to yet another petit dérive from the village to the

river on a Sunday morning in June.

|

| Dérive to the Aglad Valley and fish fair. |

|

| Dérive to the fish fair elevation profile. |

|

| Water delivery truck. |

Being a catch and release fly angler myself, I had mixed feelings about going to witness a fish massacre, but I wanted to be part of a cultural event that may soon come to an end. I trekked down the steep hillside with a British Sustainability professor from Anglia Ruskin University who was also visiting Sainji, and with an American expat English as a Second Language teacher from the local school in Sainji. Little did these two women know that the fish fair was truly an all-men’s event. As we approached the river there were swarms of men speedily making their way upstream on foot. This involved rock hopping and eventually wading across the river in multiple places. I was stopping to record the run up to the event with my still and video cameras and quickly lost my two companions to the crowd.

|

| Crowd of men headed up the Aglad River. |

There was a party atmosphere and no formal organization whatsoever. Nevertheless, men were helping one another across the stream, sons carrying large, hooped nets for their dads, men lounging on the rocks in the shade, and boys jumping from rocks into the deeper parts of the river. I was told the poison would be dumped into the water about 1 pm by one guy. Another said 2 pm, so I perched myself on a large boulder above the fray to watch, wait, and to be at a good vantage point when the “fishing” started.

I got a message that the poison was being put in the water about 200 m (218 yards) upstream and seconds later men started whistling and hollering and the guys who had been casually standing in the river with nets positioned themselves into ready mode. Then men started coming running down the riverbank. They had caught fish up top and were moving downstream to catch more. Like a great movement of ants, or a migration of reindeer herds, more and more men poured down from upstream.

|

| Nets across the Aglad River. |

|

| The rush downriver to catch fish as the poison travels. |

|

| Men fished under every rock, nook, and cranny, sometimes by hand. |

|

| Some men fished with smaller nets, out of the main river current. |

|

| His catch in a pouch tied around his waist. |

Every gap between nets became occupied with men trying to catch fish. They were feeling around under rocks along the shoreline to fill the pouches many of them had strapped around their waists with as many fish as possible. I saw a few larger fish, but most were minnow size. On occasion someone would toss a snake up on the shore and someone else would beat it to death with a stick, then toss the dead snake at a friend or cousin or complete strangers, eliciting a wild frenzy of scattering men and boys. Guys with nets would climb out of the river to empty their nets. Again, most of the fish where no larger than a man’s pinky finger, but they kept all of them. After a man with a net would go through his pile of riverweed, and mini-fish, crustaceans, river bugs of all make and model, he would head back to the river for more. Often a scavenger boy would come along and sift through the abandoned piles of weeds and would find even smaller fish the guy who dumped his net had overlooked.

|

| Hauling in the catch from a large hoop net. |

This went on for well over two hours while I observed and took

pictures. I was struck by the fervor as well as by the total annihilation of

the aquatic ecosystem. While I found it sad that boys were scavenging

minnow-like fish from the leftovers like some post-apocalyptic movie scene, I thought

this is their celebration, it is their way of doing things, the fish population

must regenerate itself or there would be no annual maun mela.

|

| Showing off his catch to a friend on shore. |

With my drinking water running short and the temperature climbing I set out back downstream to see if I could find my dérive companions. I only tolerate crowds and cities. Intriguing for a short time, but at some point, I want to be away from them. I wanted to be away from this incredible mass of thousands of men. On my way back downstream I encountered drummers and musicians playing music and men dancing all around them. While men were still seriously fishing with nets, the nature of the maun mela had shifted to a downriver-moving dance party. I joined in for a bit, took pictures and video, but then the jostling by hundreds of men was enough (trying to dance in what is effectively an outdoor mosh pit lite, on slippery rocks while holding cameras quickly becomes more burden than fun).

My dérive companions appeared with an entourage of men

from Sainji, the only two women in sight, dancing with the crowd. About as

quickly as they appeared they disappeared again into the horde of men still

moving downstream. As I got toward the end of the fishing and the riverbanks

widened there were some families and women, a few makeshift food vending shops

had been set up, and the party atmosphere continued. I gave up on finding my friends

and began the arduous hike up the steep mountainside along the crisscrossing goat

trails.

|

| Aglad River valley. |

The maun mela was on television news that evening. It was

that big of an event. I am glad I was able to be a welcomed observer in a local

tradition before it becomes drown out by a lake designed to support people

hundreds of kilometers away, yet that will keep the local fish population from

being harassed.

2022 Maun Mela YouTube Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_O7EYrYLkjM (shows making of poison)

2022 Maun Mela YouTube Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M6EzYArO_Qg

2019 Maun Mela YouTube Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMsEGFNgXFc

2018 Maun Mela YouTube Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=87dk-QpkgEs

Five Everyday Events

I will never work for Mountain Sobek. But that is okay. These types of experiences may have never occurred ‘twere I a guide or photographer trying to sell a place in a glossy trekking brochure. I would have likely focused on the extraordinary, the exotic, that which one might find posted in today’s social media. Through the text and images here I have been able to narrate my experience and reflections on five events of the many that were part of my time in the Himalayan foothills of Uttarakhand, India to present in-context views of the culture of the region that is grounded in the Yamuna River and part of a deep map. Bodenhamer et al., in Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives (2015, p. 3), explain deep mapping as:

…a finely detailed, multimedia depiction of a place and the people, animals, and objects that exist within it and are thus inseparable from the contours and rhythms of everyday life.

For me coming across women carrying firewood barefoot, or wearing plastic sandals, at an elevation in which I could barely breathe was an unusual and extraordinary event. Walking to a temple with thousands of devout Hindus alongside a river-carved Himalayan mountain valley was an extraordinary event. Taking part, with 10,000 men, in an annual cultural fair steeped in nature was an extraordinary event. Sitting on the porch of a Kharsali village elder, drinking tea was an extraordinary event. However, for the people I described these activities and events were simply everyday life and I but a blip in a moment of those lives. Yet, it is just that very ordinariness that is important and often overlooked. Geographers “neglected the everyday in their enthusiasm to document the exceptional, the new and the exotic” (Holloway & Hubbard, 2001, p. 36). Perhaps the tables were actually turned—I was the exotic in this narrative, giggled at by barefoot mountain-hardened women, asked if I had made the complete yatra as a middle-aged foreigner (“if he can do it I can”), or as a front-porch spectacle to show the neighbors what was found wandering the terraces. Here I have provided my personal narrative in an effort to highlight a place and the people who live within it, going through their everyday rhythms, so they become people to you, not just as others, over there somewhere.

|

| Working from my "office" in Sainji Gaon, Uttarakhand, India. June 2022. |

References

Bodenhamer, D.

J., Corrigan, J., & Harris, T. M. (2015). Deep maps and spatial

narratives. Indiana University Press.

Debord, G.

(1958). Theory of the derive. Internationale Situationniste, 2. https://rohandrape.net/ut/rttcc-text/Debord2006e.pdf

Gearhungry

Staff. (2019). The best barefoot running shoe. https://www.gearhungry.com/best-barefoot-running-shoes/

Haberman, D.

L. (2006). River of love in an age of pollution: The Yamuna River of

Northern India. University of California Press.

Holloway, L.,

& Hubbard, P. (2001). People and place: The extraordinary geographies of

everyday life. Pearson.

Johnson, W. J.

(2009). A dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press.

Nugteren, A. (2008).

[Review of the book River of love in an age of pollution: The Yamuna River of Northern India, by D. L.

Haberman]. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture, 2(4),

530-531.

Stark, F.

(1937). Baghdad sketches. John Murray.

Uniyal, A.,

Shah, P. N., Prakash, C., Gangwar, D. S., Dhar, S., Mishra, S. P., Sharma, S.,

& Malik, G. S. (2012). Anthropogenically induced mass movements along the

Dharasu–Yamunotri route. Current Science, 102(6), 825-829.

Comments

Post a Comment